Motivation for Losing Weight: Dieting Without the Struggle

Key Takeaways:

The best diet for weight loss is one you can stick to for the long term.

Once you’ve chosen a diet that makes the most sense for you, adopting a flexible approach is key to achieving and maintaining weight loss.

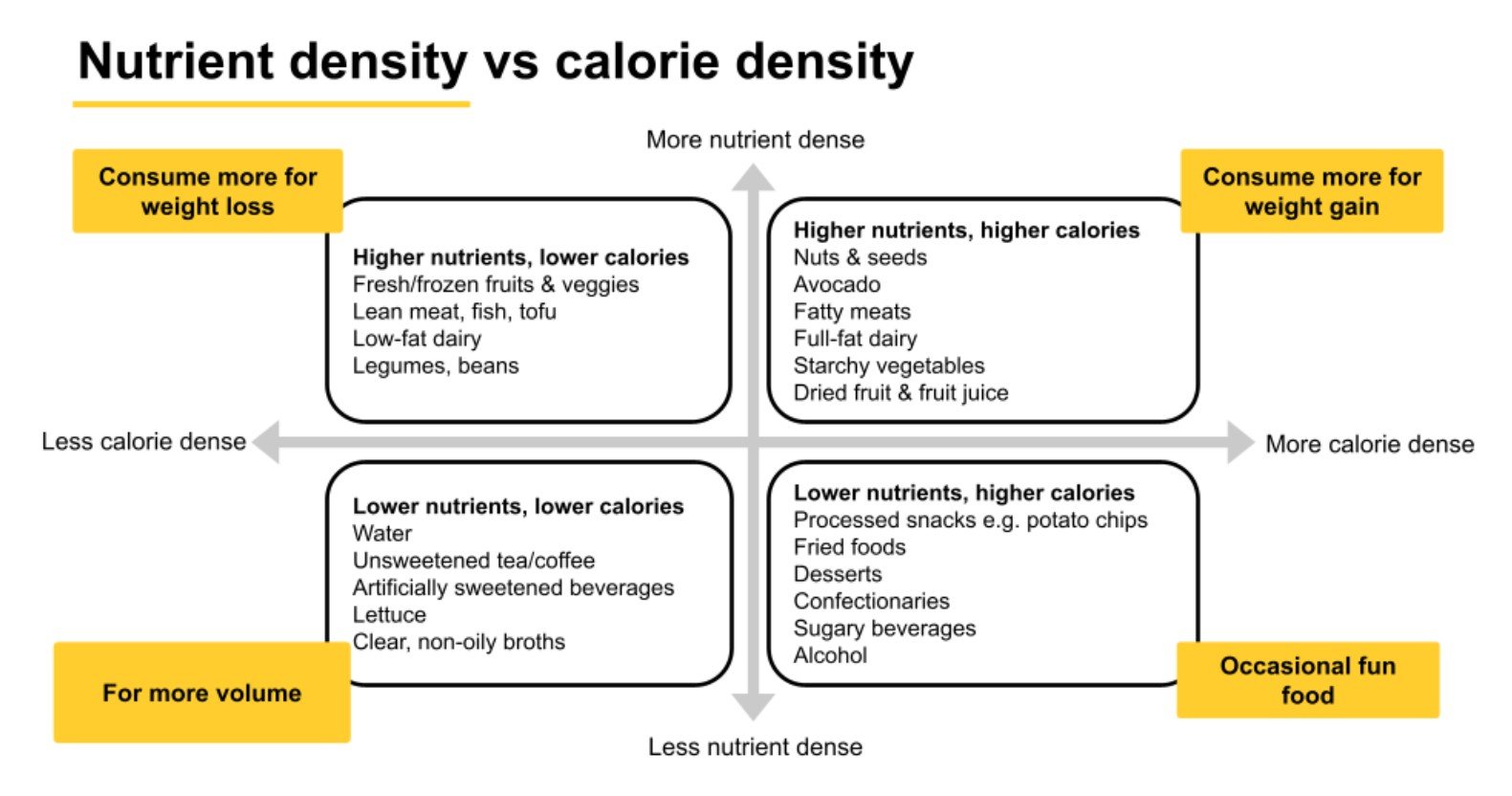

Understanding where a particular food lies on the nutrient- and calorie-density quadrant helps you easily make smart food swaps without compromising overall diet quality or weight loss results.

The bulk of your meals should consist of high-nutrient, low-calorie, and low-nutrient, low-calorie foods. You don’t have to eliminate high-nutrient, high-calorie, or low-nutrient, high-calorie foods — just make sure they make up only a tiny portion of your diet.

Plain steamed chicken breast. A fistful of boiled broccoli. Oh, and let’s not forget the brown rice. Eat on repeat for breakfast, lunch, and dinner — Mondays through Sundays. This is likely the “template” weight loss meal plan that pops into your mind when you think of going on a diet.

With this eating pattern, you’re almost always guaranteed weight loss success because of how few calories you eat.

But the problem doesn’t lie with its efficacy. It’s sustainability. Having chicken breast, broccoli, and brown rice for days on end makes for a dreadful diet that most people can’t keep up with over the long term, ultimately resulting in weight regain.

What’s the alternative then?

How to (actually) stay on track with your diet

The “secret” to staying on track with your diet is not more self-restraint or discipline.

Instead, it’s knowing two things.

First, there’s no such thing as a single, best diet for weight loss. Longitudinal trials and meta-analyses show that, on average, both low-carb and low-fat diet approaches yield similar weight loss results.

Other studies pitting various diets, from plant-based diets to intermittent fasting, against each other have also singled out consistency in achieving a calorie deficit and overall dietary quality as the biggest drivers of weight loss success rather than any specific eating pattern.

Learn more about using intermittent fasting and plant-based diets for weight loss in these articles: Plant-Based Eating: Does It Help With Weight Loss? and What Does Science Say about Using Intermittent Fasting for Weight Loss?

Second, no matter your choice of dietary approach, flexibility pays off.

To expand on that, there are broadly two ways an individual may approach dieting:

Rigid restraint: A dichotomous, all-or-nothing approach to eating typically characterized by the complete avoidance of “fattening” calorie-dense foods (“junk food”), regimented calorie counting, and fasting.

Flexible restraint: A more “balanced” dietary approach characterized by conscious and intentional food choices, monitoring portion sizes (“junk foods” are permitted in limited quantities rather than avoided entirely), eating to satisfaction, and compensating by eating more or less when needed.

These two approaches predict very different outcomes. While rigid restraint is associated with a greater tendency to overeat and poorer weight control, flexible restraint predicts better weight control and reduced overeating.

Take, for example, this 2004 study published in the International Journal of Obesity.

The researchers had 6,857 participants from a commercial weight loss program attend (primarily) doctors-led counseling sessions to induce lasting, positive changes in the participants’ dietary behavior.

A key behavioral characteristic measured was whether the participants had rigid (where periods of strict dieting alternate with periods without any weight control efforts) or flexible control of eating behavior (a graduated, “more or less” approach to eating and weight control).

At the 3-year follow-up mark, researchers found that participants who’d adopted a more flexible control of eating behavior — and maintained it — had a higher probability of successful weight reduction.

This finding aligns with a more recent 2013 study published in Eating Behaviors.

In 106 women who’d initially lost approximately 10 kg of their initial weight and were hoping to sustain their weight loss during the six-month study, it was found that:

Flexible restraint: Associated with more weight loss and better weight loss maintenance

Rigid restraint: Associated with less weight loss

So, ultimately, here’s how to stay on track with your diet:

Choose a diet that makes the most sense for you; prioritize one that suits your dietary preferences and/or restrictions (e.g., don’t choose the Mediterranean diet if the taste of olive oil makes you want to throw up)

Adopt a flexible approach to dieting to maximize your chances of keeping the weight off long-term

Understanding nutrient density and calorie density

Now, it’s important to note that dietary flexibility doesn’t mean eating whatever and however much of it you want.

While you don’t have to obsess over categorizing everything you eat into specific macronutrient groups or counting calories, you should still have a rough idea of where a particular food lands on the nutrient density and calorie density quadrant.

This helps you easily make smart food substitutes in your fat-loss diet whenever you get bored of eating something or when an ingredient becomes inaccessible for cost or availability reasons.

For those wondering, here’s what “nutrient density” and “calorie density” mean:

Nutrient density: Refers to the amount of beneficial nutrients in a food in proportion to its energy content. For example, just think of a medium-sized banana and Haribo gummies. Even if served in portions that provide the same calories, they have very different contents of added sugar, fiber, vitamins, and fats. A hundred calories of a banana will be more nutrient-dense than an energy-matched serving of Haribo gummies.

Calorie density: Refers to the amount of calories in a given amount of food, usually expressed as calories per gram. Calorie-dense foods contain more energy per gram, meaning you’ll eat more calories than the same portion of low-calorie-dense foods. For example, 1 cup of low-fat milk vs. 1 cup of ice cream; the ice cream is much higher in calories due to its fat and sugar content.

Diving into the four quadrants

Credit: @zhiling_nutrition

Now, there’s a reason why we mentioned “quadrant” when talking about nutrient density and calorie density.

While it may be tempting to apply the two concepts in a “black and white” way, it’s not always that high-calorie-dense foods always contain few nutrients or that nutrient-dense foods are necessarily low in calories.

Let’s explore each of the four quadrants in more detail:

High in nutrients, low in calories: These foods should make up the bulk of your diet when you’re trying to lose weight. They provide your body with more health-promoting nutrients that are usually not consumed enough — such as protein, fiber, unsaturated fatty acids, potassium, calcium, iron, and vitamin D — in fewer calories. Examples include fruits and vegetables (e.g., a bag of frozen broccoli from NTUC), whole grains, low-fat or fat-free milk and/or soy products (e.g., beancurd), seafood (e.g., steamed barramundi or any lean fish), lean meats, eggs, and legumes.

Low in nutrients and low in calories: These foods are helpful in “bulking up” your intake without adding too many calories to your diet. And why would you want to do that? For satiety’s sake: research shows that the volume of food consumed could affect how full you feel through stimulating mechanoreceptors or chemoreceptors in the gastrointestinal tracts, independent of its energy content. Examples of foods that fall into this quadrant include water, , black coffee (e.g., kopi o kosong), and certain water-rich fruits and vegetables (e.g., iceberg lettuce and cucumbers).

High in nutrients and calories: Eat less of these foods when trying to lose weight. While these foods provide significant amounts of important nutrients, they’re also relatively high in calories. Examples include nuts, seeds, and some dairy products, like heavy cream. It’s important to remember that the overall nutritional value of foods can change depending on how they’re prepared, cooked, or processed. Just think about potatoes. Eaten on their own, potatoes are relatively high in nutrients and low in calories. But cooking potatoes with a generous amount of butter and milk, then drowning it in mushroom gravy (i.e., mashed potatoes)? That’s when it slides right into the high in nutrients, high in calories quadrant. Other local foods you’ll find parked squarely in this category include peanut butter toast and Taiwanese braised pork rice bowl (lu rou fan).

Low in nutrients, high in calories: Contrary to popular belief, you don’t have to eliminate these foods from your diet when trying to lose weight. You just have to ensure you eat them only occasionally and that they make up only a tiny part of your diet. In fact, research shows that planned hedonic deviations (a fancy term for indulging in high-calorie, low-nutrient foods) during dieting boosts motivation, enjoyment, and long-term diet adherence. Examples of high-calorie, low-nutrient foods include fried foods (e.g., Arnold’s fried chicken) and ultra-processed foods (e.g., cakes and biscuits).

Dive deeper into processed foods’ impact on your health in this article: Processed Food: What Is It and Why Is It Bad for Metabolic Health?

Prioritizing high-nutrient, low-calorie and low-calorie, low-nutrient foods in your everyday meals can help you take a step in the right direction.